Archives

The Mysterious Case of Ernest G. Lemcke

By Lauren Maddox

Sometimes I like to pull back the curtain a bit for you– show you some of the behind-the-scenes work that goes on unseen at the AGSL. I was given a special project a few months ago that I thought the readers of this blog would be interested in hearing about.

Some things about me you need to know: I love puzzles and I have never seen Mission Impossible. Most of the AGSL staff loves puzzles; we are currently working on a 4,000 piece puzzle (which you can see if you visit us!). Generally, my work at the AGSL has me at a desk writing– that’s my job. But sometimes someone gives me something different to work on.

Susan Peschel stopped by my desk with a nondescript beige box.

“Your mission, should you choose to accept it–” she stopped to ask me if I remembered Mission Impossible. I didn’t, but I had at least heard the quote before. Susan told me that she had a puzzle for me (and that it might explode once she walked away).

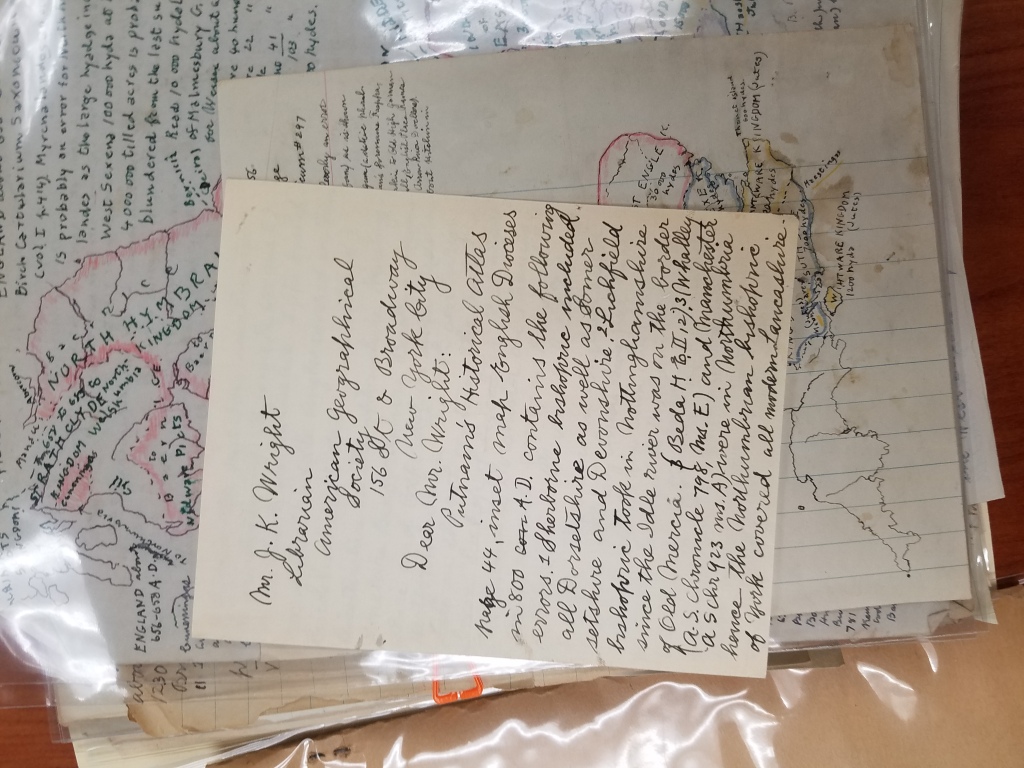

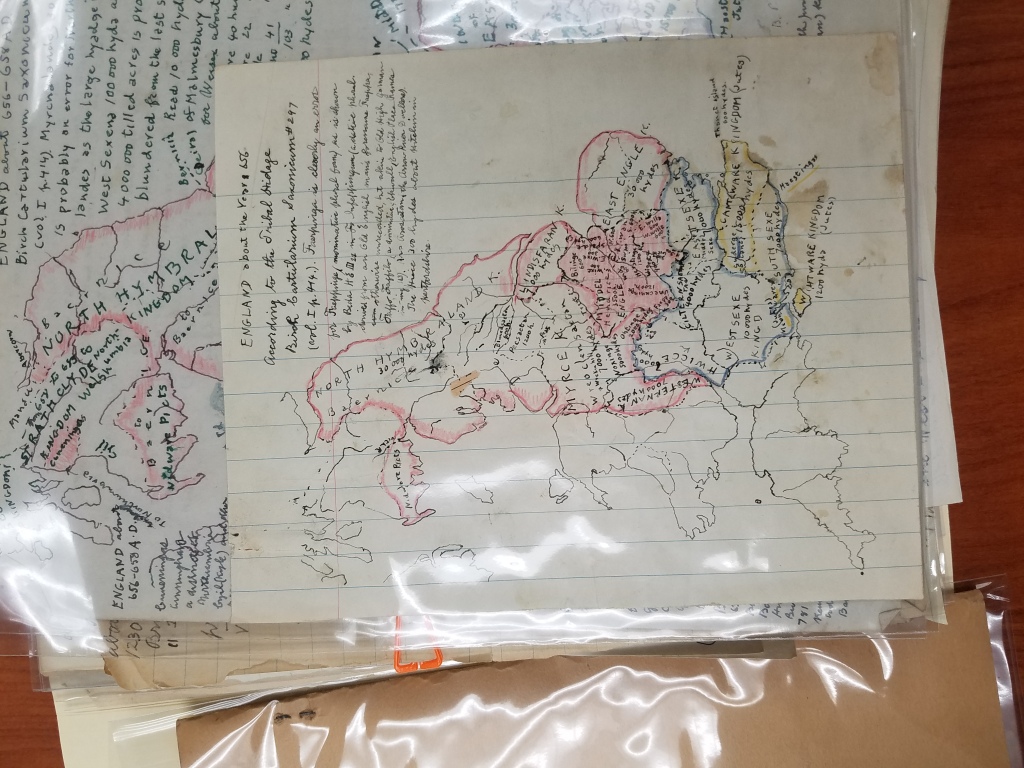

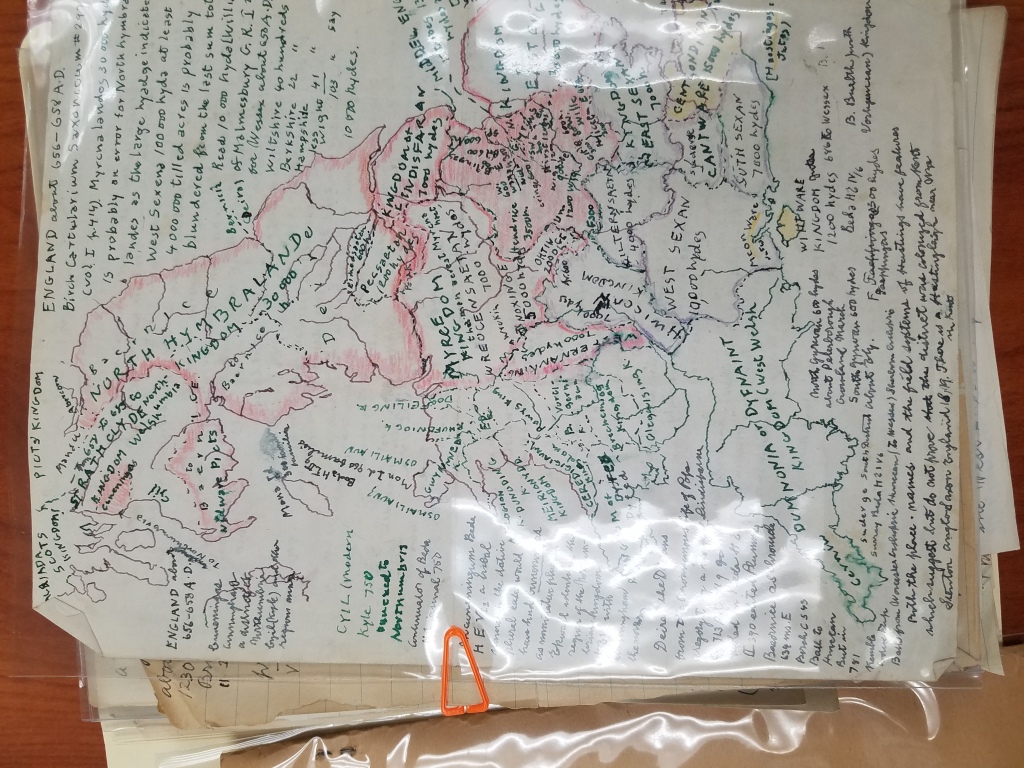

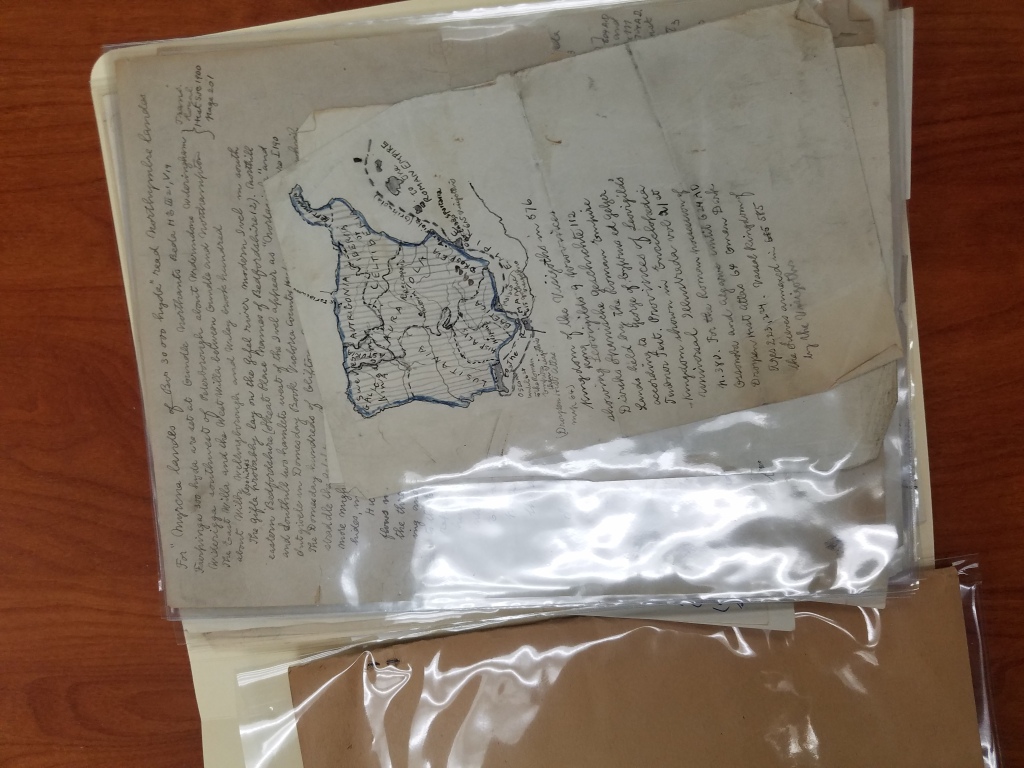

The problem with the box, which had traveled with the AGSL’s collection from New York to Milwaukee in the 70s, was that it had never been archived. The papers in the box were unsorted– no one even knew what they were. By all appearances, the collection of handwritten pages and letters seemed random. There were maps in the pile, but they were either hand-drawn or, stranger, road maps that had been drawn over. My mission (and I did accept it) was to figure out what we had and then to put it into some semblance of order.

We didn’t know much, but we did know his name: Ernest G. Lemcke. We knew he was a card-carrying member of the American Geographical Society of New York because we have a record of his membership dues:

He wrote a trove of letters to Ena L. Yonge and John K. Wright. He bought a roadmap in 1926 and hand-drew a medieval military event in England from the 1300s. He was a book publisher in New York– which I discovered because some of his stationery had letterhead from Lemcke&Buechner, “Booksellers, publishers, importers.”

Part of the trouble with deciphering the box was figuring out what was meant for who. The maps were easy– Ena L. Yonge was map curator for the AGS of New York at the time, and his maps often came with a letter explaining what they were. But the partial manuscripts, many handwritten first drafts, and article corrections for the AGS’s periodical were mysterious and dense.

After many fruitless Google searches, I learned a few things about Lemcke: besides being a book publisher, he was also a historian with several books out, many specifically interested in the “Tribal Hidage” in Wessex. As it turns out, the University of New Hampshire also has a collection of Lemcke papers! Which was how I tracked down some of his publications and discovered that the many handwritten pages about a “tribal hidage” and the first English Census were partial drafts of his later, completed publications.

Now that I had a better idea of what we had, I came to the next part of the puzzle: putting it in order. I started with separating the things that were obviously addressed to Yonge or Wright. Maps were obviously meant for Yonge, and corresponded with letters that he had sent. John K. Wright was once director of the AGS of New York, but that didn’t help place many of Lemcke’s letters. But as it turned out, before he was director, Wright was the editor of the AGS’s regular publication from 1920-1956. This was exactly the period of time Lemcke was writing. The periodical corrections, then, seemed to be for the editor of the publication. And after reading Lemcke’s letters, I found him explaining corrections to his manuscript to Wright.

Once the letters were sorted by recipient, I started to put them in a chronological order. Some of the letters were dated– those were easy. But many of the letters weren’t dated. For several of them, I found a reference he made to an article he had just read, which helped me place it in the chronology. But many more had to be dated by their relationship to the other letters, which made for some puzzling work.

After finishing the work of putting the box in order, it was time to have it officially archived. This was definitely out of my expertise, so I reached out to fellow graduate intern Georgia Brown, who consulted our curator, Marcy Bidney, about what to do with the box.

Soon, the Lemcke papers will be officially archived! Since all of his correspondence was addressed to Ena L. Yonge and John K. Wright, the letters will be incorporated into their existing correspondence collections, cataloged, and made available for viewing! And now, with a little puzzling, we have put a years-old AGSL mystery to rest.

Mornings in Mexico: A Short History of Travel Literature

By Lauren Maddox

In 1919, still recovering from a nearly fatal bout of influenza, D.H. Lawrence fled England. He had been staying in Derbyshire with his wife Freida, finishing “The Wintry Peacock” and hiding from authorities. The couple was destitute; his most famous novel The Rainbow had been banned on obscenity charges and the government was using the Defence of the Realm Act to openly, and often violently, harass Lawrence for his anti-militarism and Freida’s German heritage. Sick, and barred from publishing, Lawrence resolved to undertake his “savage pilgrimage.” His self-exile from England was funded by an ancient, and very British, literary tradition: travel literature.

Photo of Lawrence by Lady Ottoline Morrell 29 November 1915

Despite these dire beginnings, Lawrence produced several gems during his travels: Twilight in Italy, Sea and Sardinia, Etruscan Places, and in 1927 Mornings in Mexico. The AGSL has a 1927 edition of Mornings in Mexico as well as a collection of travel writings from across time time and space, including dozens of travel books exploring Mexico and Latin America.

But the tradition of travel literature has existed as long as we have been traveling. Petrarch, climbing Mount Ventoux in 1336, accused his traveling companions of being frigida incuriositas–men with cold curiosity. The climb became a metaphor for Petrarch’s life, and he used his physical and visual experience of the landscape as a way to meditate on his own moral climb. UWM professor emeritus H. James Shey translated Petrarch’s Itinerarium, which outlines Petrarch’s proposed route for Giovanni Mandelli’s pilgrimage to the Holy Land in 1358. The Itinerarium focused primarily on the geography and path Mandelli would travel, but also included references to local history and Petrarch’s own spiritual experience as a pilgrim. The AGSL has a signed copy of Shey’s translation (which includes his own commentary on the Itinerarium) in the collection.

Travel literature was a well-loved genre before tourism took hold as a social standard; travel literature became a way for people to explore new places that they would never travel to themselves. Travel writing has taken many different forms over the years– in the 2nd century, Pausanias wrote his Description of Greece as Greece was being incorporated into the Roman Empire. The books attempt to capture the glories of Greek culture even as it began to shift into obsolescence by dedicating entire books to describing specific cities and regions, their geography, architecture, and religion. This multi-volume 1898 edition was translated by J.G. Frazer— the AGS purchased it as first edition from Macmillan & Co. the year it was published.

Travel writing continued to develop– travel diaries became popular during the Song Dynasty in China and Medieval Arabic literature. In the West, the genre became increasingly popular as exploration became a cultural priority; The Travels of Marco Polo transported readers to a great unknown East, Christopher Columbus’s journals became fascinating narratives of discovery, and maritime travelogues expanded the imaginations of the general population. But the tradition, especially in Europe, became steeped in colonialism.

In Mary Louise Pratt’s Imperial Eyes: Travel Writing and Transculturation, she asks “how travel books written by Europeans about non-European parts of the world created the imperial order for Europeans “at home” and gave them their place in it.” Europe’s economic and political growth in the 18th century opened the door to imperialist ideals, and in time the colonization and exploitation of countries by Europe. Travel literature written by European authors became a way for Europeans at home to imagine their place in the Empire and imbued them with a sense of “ownership, entitlement and familiarity” that allowed them to idealize European expansion as a moral quest to spread civilization to “uncivilized” hinterlands beyond their own borders. Travel writers became the eyes through which Europeans viewed the rest of the world, complicating the role of travel writing in literature and the colonial to post-colonial world. The act of viewing and recording became a way for colonizing countries to express ownership over the “domestic subjects” being viewed and recorded.

Provincia del Chocó. Interior de las habitaciones de los Indios, circa 1853 from Nancy Applebaum’s Mapping the Country of Regions: The Chorographic Commission of Nineteenth Century Columbia Click the link for a better view

So, when Lawrence left England and wrote about his travels to feed himself during his “savage pilgrimage” and long exile, he joined a long tradition of Europeans who, voyeuristically, observed and recorded the countries beyond their own borders as a way to stake their claim. Even Lawrence, rejected by his England and forced to wander, couldn’t separate himself from a long tradition of literary Imperialism. But travel writing continues to thrive: travel guides, tourism blogs, journals and memoirs connect people to places they might be going or have never been. We still use travel literature as a way to reflect on our own lives, like Petrarch, to see beyond ourselves, and experience new places. Travel literature has a long, and sometimes detrimental, history– but, Lawrence assures us, “still, it is morning, and it is Mexico. The sun shines.”

The Love-Life of Dr. Kane

By Lauren Maddox

Click the link to see this Portrait of Kane from the Edmund Mills Scrapbooks in the AGSL Archives

Elisha Kent Kane, who appeared in last week’s post about the lost Franklin expedition, lived a life of adventure, and his harrowing escape from the arctic became an iconic expedition in the era of romance and arctic exploration. The accomplished explorer died tragically after his return from the second Grinnell expedition; extreme climate and malnutrition had wreaked havoc on his health. He died just two years later in Havana, Cuba, where he had traveled with his family in the hopes of recovering in the warmer climate. His life of intrigue and excitement didn’t end in the arctic, however; apparently Kane also had a titillating love life. After his death in 1857, a rather scandalous legal dispute began: Margaret Fox, claiming to be Kane’s secret wife, took Kane’s family to court for withholding her inheritance.

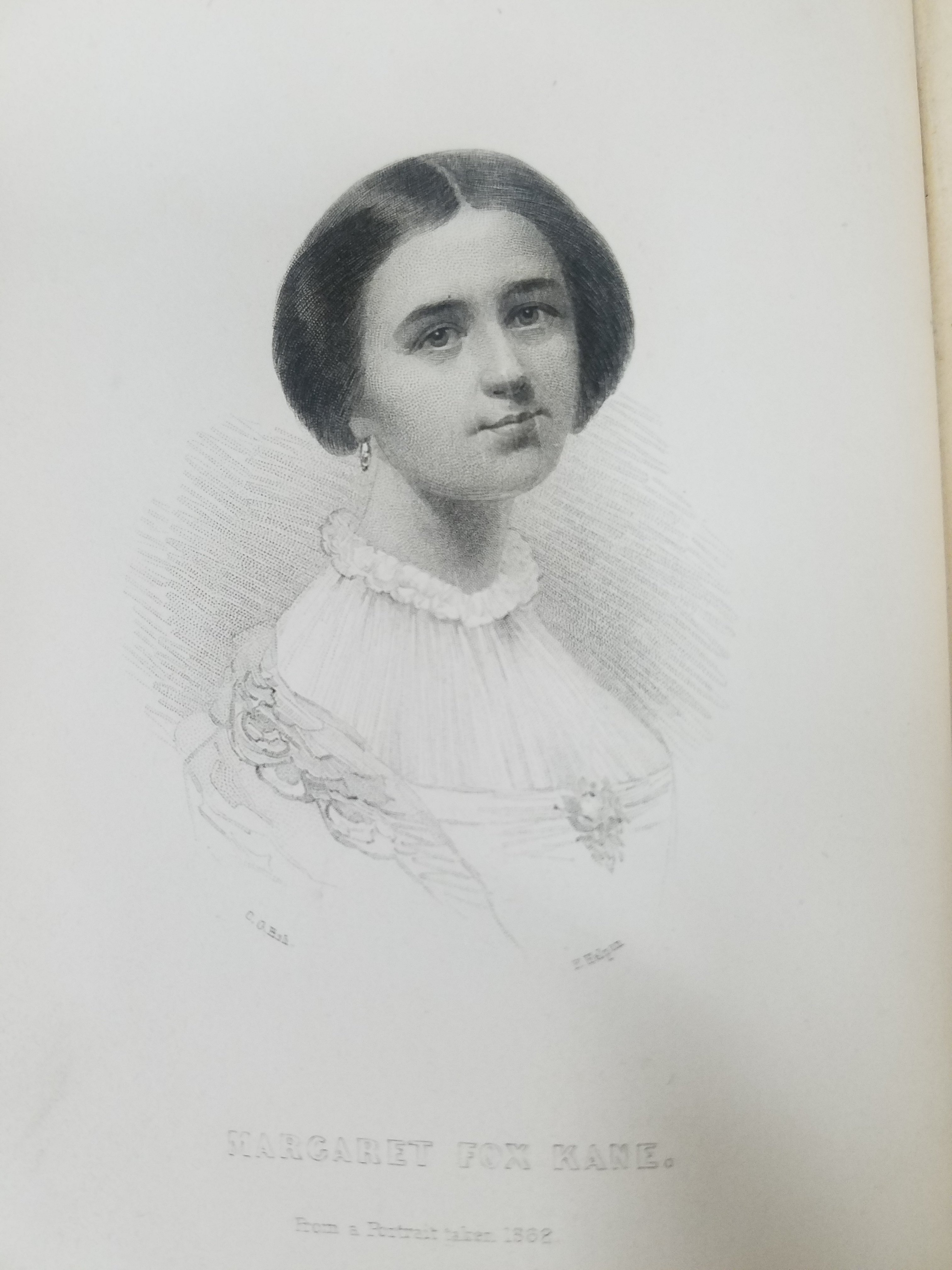

Click the link to see the Portrait of Margaret from The Love-Life of Dr. Kane

Margaret Fox was the middlest of the famous spiritualist Fox sisters. Margaret and her younger sister became famous in 1848 for supposedly communing with the entity that haunted their house in Hydesville, New York. The girls rocketed to fame and began giving demonstrations of their spiritual powers the next year. By 1850, the girls were holding public seances in New York. She and her younger sister continued their journey to spiritualist stardom under the management of their oldest sister Leah; the trio would spend years enjoying success as the centerpieces of seances attended by the well-to-do and famous.

The AGS Library has in its rare collections a first edition copy of Margaret’s tell-all book The Love-Life of Dr. Kane, in which she claims to have secretly married Kane and publishes their personal correspondence to prove it. The book was gifted to the AGSL in 1922 by Edmund Mills from his collection of arctic books. The book, published in 1866, is prefaced and introduced by an unnamed author sympathetic to Margaret’s position in her legal battle with the Kane family and includes a memoir giving a narrative telling of the illicit love-match.

The preface first apologizes for the indecency of publishing love letters and “that which was never intended to meet the public eye,” but goes on to explain that the publication of these private letters, considered too “sacred” by Margaret to publish previously, will save her reputation from the slander she suffered by keeping them private. According to the preface, Kane had left a small inheritance to Margaret as his wife. Their marriage was vehemently denied by the surviving Kane family, and any mention of it in the press was quickly disparaged. Margaret, widowed and without an income, was forced confront the Kane family about the sum left to her by her late husband. After several disputes, several of which involved Elisha Kane’s brother breaking financial agreements, Margaret decided to publish the letters.

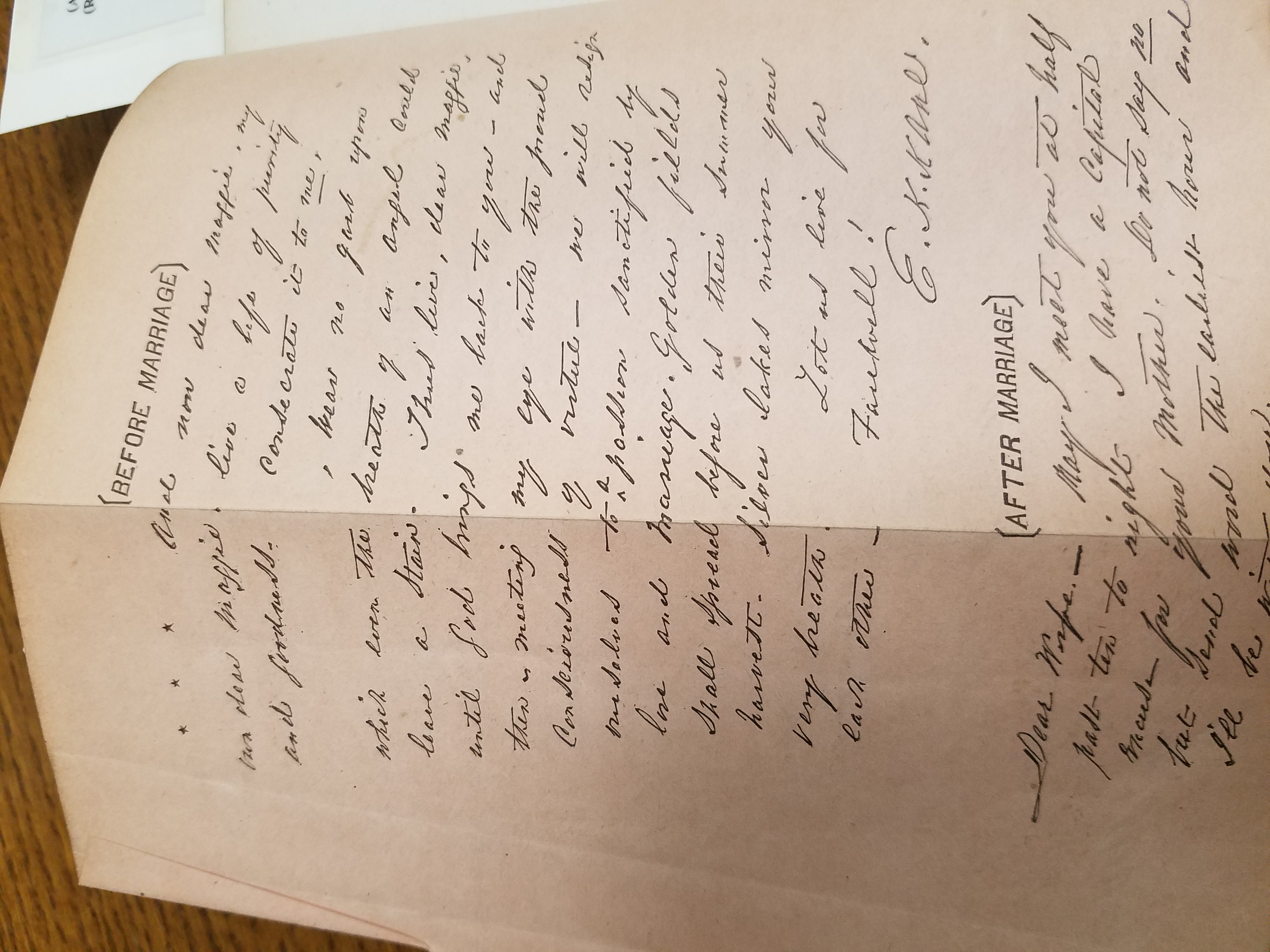

Fold out copy of letters in Kane’s handwriting tucked between the preface and introduction

Kane’s signature

The introduction casts Kane and Margaret as star-crossed lovers kept apart by her occupation as a spiritualist, lack of social position, and his own family’s objections to her reputation. The anonymous author, rather romantically, declares, “How deep and strong that love must have been, to come off victorious from such a conflict!” Then finally, the Memoir chapter begins with the story of how the two met and the letters that they exchanged over the course their courtship. The author describes Kane’s falling in love with Margaret at first sight when he found her in Webb’s Union Hotel bridal parlor the autumn of 1852, preparing for a seance. Their epistolary romance began just days later when Kane slipped Margaret a note asking, “Were you ever in love?” And Margaret replied, “Ask the spirits.”

The romance, as told by the collection of letters, was tumultuous. Kane often denounced Margaret for not being affectionate enough, for continuing her work as a medium, or any number of sundry offenses. And his long absences, during which he sent Margaret to school to be educated until his return, were also a struggle. Though Henry Grinnell often wrote to Margaret to update her about Kane’s progress, the long separations created even more tension between the two. His family rejected Margaret so vehemently that her mother was forced to bar Kane from seeing her for fear of Margaret’s feelings or reputation being injured. Kane continued to seek Margaret out, and even asked her to marry him when he saw her on the street. She refused, but the press caught wind of their so-called engagement and maligned her in the papers. Kane never officially denied their engagement, which helped the gossip continue. Years passed, but in 1856, after Kane’s return from the second Grinnell expedition and the death of one of his close friends, Kane proposed to Margaret again. This time, more officially. But the two would not actually be married until days before he left for Cuba to recover his health– in the Fox’s parlor, Kane declared, in front of Margaret’s mother as their witness, that they were husband and wife. The book cites several legal precedents for this kind of common law marriage, assuring readers that the two were rightfully, if not publicly, married that night. The tone of Kane’s letters changes after this; he begins calling Margaret his beloved wife, but is filled with dread by his continually declining health. He tells Margaret that his greatest fear is dying away from her– which is, of course, what happens. And their marriage, which they had both vowed to keep secret until his return from Cuba, was never officially acknowledged by the Kane family. Margaret converted to Catholicism after Kane’s death and spent her days disavowing her own family’s legacy as mediums.

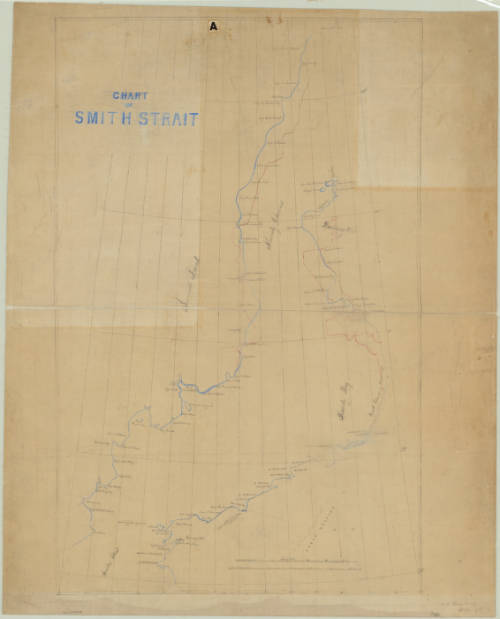

The introduction of The Love-Life of Dr. Kane claims that a man’s love letters “[reveal his] inner life and soul.” Elisha Kent Kane was a larger-than-life man who gave his life to the pursuit of discovering the unknown. The correspondence collected and published by Margaret Fox show us that Kane was also just a man, with a life and love beyond what we know. The AGSL has several maps by Kane in its collection, reminding us of his many contributions to the American Geographical Society. Below are just some of the items in the AGSL archives: his 1853 circumpolar charts and his surveys of the arctic during the Grinnell expeditions.

AGS of NY Archives Grant-Supported Processing Project Completed

by Bob Jaeger and Susan Peschel

A three-year project to organize and process the American Geographical Society of New York Archives, funded by a grant from the Andrew Mellon Foundation through the Council on Library and Information Resources (CLIR), has been completed.

The CLIR grant funded a full-time archivist and part-time student employees to work on the collection, which contains the records of the Society, the only organization focused on bringing together academics, business people, those who influence public policy (including leaders in local, state and federal government, state and federal government, not-for-profit organizations and the media), and the general public for the express purpose for furthering the understanding of the role of geography in our lives.

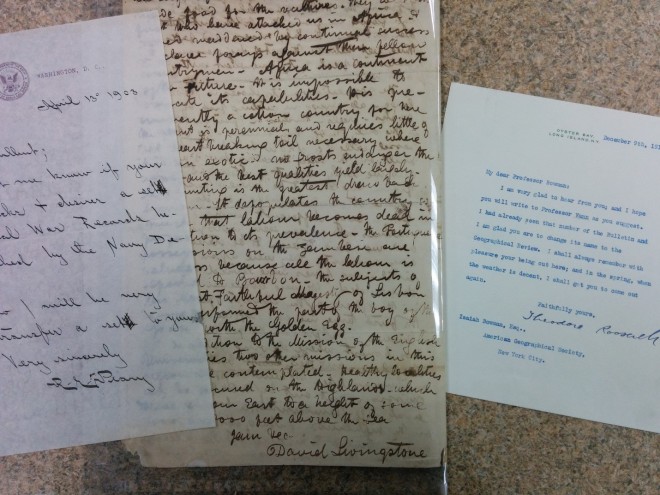

The materials date from the Society’s founding in 1851 and include approximately 350 cubic feet of material, with documents relating to well-known figures in American exploration and the larger field of geography from the mid–nineteenth century through most of the twentieth.

Highlights include log books, diaries, photographs, and artifacts of early Polar expeditions, such as the papers of Robert E. Peary (who served as President of the Society), the American flag carried by Capt. Charles Francis Hall on his second Polar Expedition, and correspondence with such individuals as David Livingstone, Franklin D. Roosevelt (an AGS councilor), Charles Lindbergh, and William H. Seward, to name only a few.

The collection contains correspondence, publications, reports, maps, meeting minutes, ledgers, and records on expeditions, explorers, and other geographic organizations and activities. For more information, please contact the American Geographical Society Library at 414-229-6282 or via email at agsl at uwm dot edu.

American Geographical Society Library Records, 1851-2013 (link to finding aid)

American Geographical Society New York Archives (link to digital collection)

The images selected for this digital collection focus on explorers and expeditions, particularly to the Polar Regions. Highlights include log books, diaries, photographs, and artifacts of early Polar expeditions, such as the papers of Robert E. Peary (who served as President of the Society) and Isaac Israel Hayes, sketches of Inuit life by Robert Flaherty, records from the Transcontinental Excursion of 1912, and correspondence with such individuals as David Livingstone, Franklin D. Roosevelt (a councilor), Charles Lindbergh, and Louise A. Boyd to name only a few. The collection also contains correspondence, publications, reports, maps, meeting minutes, ledgers, and records on expeditions, explorers, and other geographic organizations and activities. The digital collection is under development as more items continue to be scanned and added to the collection.