Russian History

Imperial Russian Black Sea Atlas at the AGSL Part II

By Josephine Miller

Black Sea Atlas

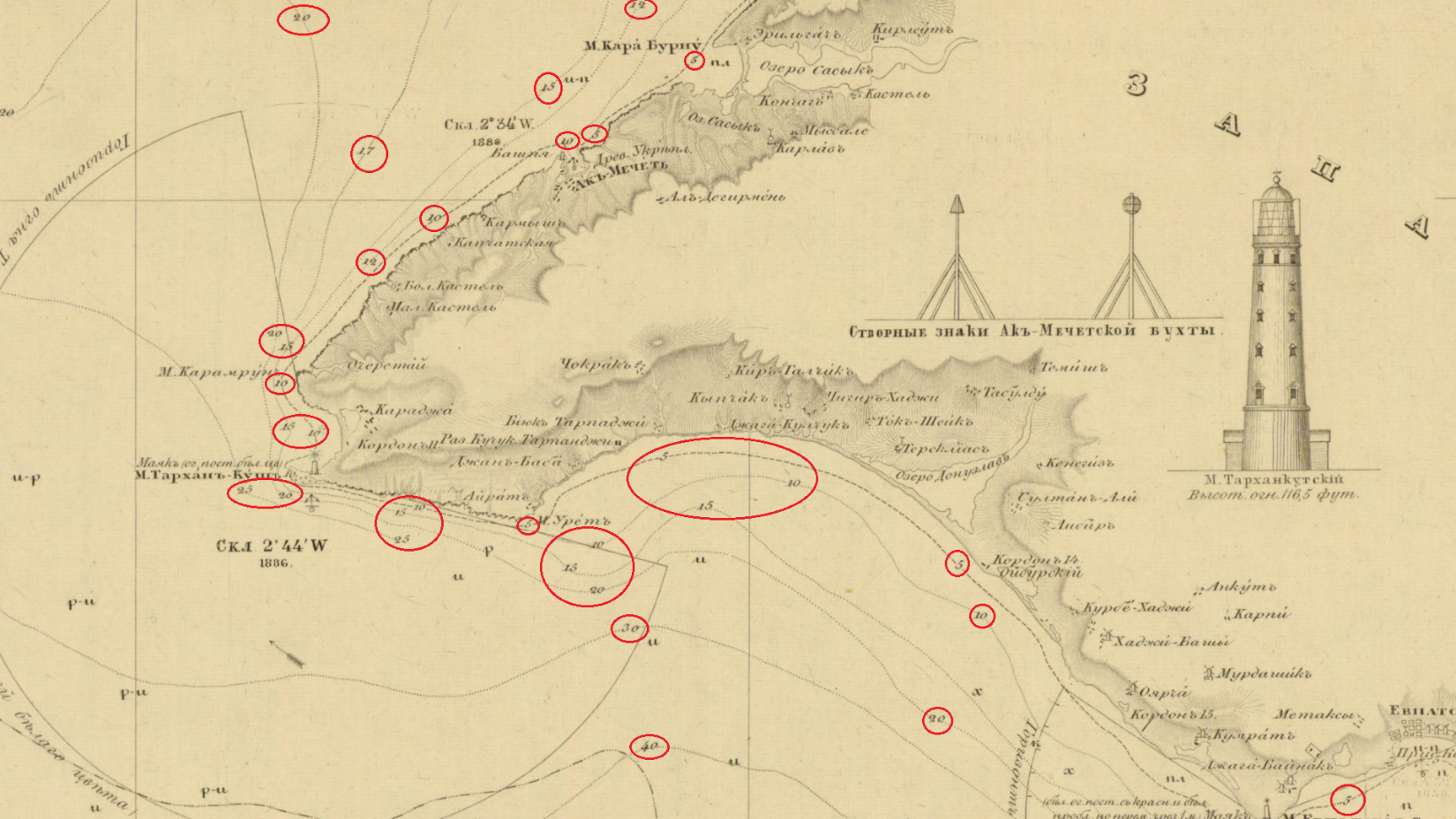

The atlas became a significant work. It would be used by the Russian military for the next 30 years.[1] Manganari’s nautical charts were used as a base for the later editions published by the Imperial Navy. Even the Soviets used Manganari’s charts as a base in the 1920s, about eighty years after the original atlas was published. These later editions are held by the AGS Library. In the AGS Library’s possession are Black Sea and Azov nautical charts that date from the 1880s to the 1920s. Illustrations and corrections were added to later editions. These illustrations include lighthouses, large buildings, sea marks, and day marks to facilitate navigation. Newer measurements of compass declination were also added. However, much of the original Manganari charts remained in the later editions. His drawing of the coastlines, topography, and bathymetry remained as a base for future editions into the early Soviet era. The soil reports given from his nautical charts remained as well. Additionally, the map scales were kept in later editions.

As for the coastlines of the nautical charts, they were drawn according to astronomical and trigonometric calculations. This can be seen virtually all of the nautical charts of the Black Sea Atlas:

“Shore is determined by trigonometric means and many astronomical observations.” From Карта Части Сѣвернаго Берега Черного Моря отъ Одессы до Мыса Херсонеса (A Map of Northern Black Sea Coast, Odessa to Cape Chersonesos). Click the link to see the entire map!

Navigational routes, drawn as sea lanes, are essential to nautical charts. To aide navigation, landmarks and seamarks are given. Manganari plotted different kinds of lines to indicate valuable information for navigation. Each chart in the atlas has almost identical legends in regards to navigation. However, there is slight variations between charts due to mountains or cultural landmarks. These cultural landmarks are usually religious, such as churches and mosques. Here is the legend from the 1891 edition of the Northern Black Sea Coast.

1. The limit for which, due to shallow water and bad soil, should not enter. 2. Equal depths on the plotted line. 3. Direction of fairway. 4. Mosque. 5. Distinctive mountain peaks, convenient for bearing. 6. Anchor place for large ships. 7. Anchor place for small and coastal ships. 8. True Meridian. 9. Magnetic Meridian. 10. Telegraph 11. Tide or Current.

One area of British influence in Russian cartography is measurement. A larger than life ruler, the impact of Peter the Great carried long after his death. His reign is reflected in the field of Russian cartography. Inspired by his tour of the West, he established in the Imperial Navy in 1696. Peter’s command to westernize Russian government brought Western cartography to Russia, military largely in mind. One major reform was to implement British measurements for military use. Consequently, almost two centuries later, the Russian Navy used the British Imperial measurements in its nautical charts. This can be seen on the AGSL’s charts. The Imperial measurements were used for distance and depth.

On this 1891 edition nautical chart of the northern Black Sea coast, the map scale uses British measurements:

On this 1891 edition nautical chart of the northern Black Sea coast, the map scale uses British measurements:

Map Scale of Карта Части Сѣвернаго Берега Черного Моря отъ Одессы до Мыса Херсонеса [Northern Black Sea Coast, Odessa to Cape Chersonesos].

Another example of British measurments is found on the same chart, depth.

“Depth of sea height measured in six-foot English fathoms – rivers and estuaries in feet.”

Circled below are the depth marks.

From Карта Части Сѣвернаго Берега Черного Моря отъ Одессы до Мыса Херсонеса (Northern Black Sea Coast, Odessa to Cape Chersonesos). Click the link to see this map in our Digital Collections!

In addition to depth, Managanari recorded the soils of the sea floor.

Карта Части Сѣвернаго Берега Черного Моря отъ Одессы до Мыса Херсонеса (Northern Black Sea Coast, Odessa to Cape Chersonesos). Click the link to see the whole map in our Digital Collections!

- Silt

- Sand

- Rock

- Silt with sand

- Silt with shells

- Large Shell

- Shell, sand in silt

- Petrified weeds

- Weeds and shells

- Plate

- Cartilage or Gristle

- Shells

Sea floor on the chart. The letters represent soils as indicated by the legend.

Later editions published after the Treaty of London (1870) include lighthouses and seamarks. Here is the Lighthouse of Tendra Bay on the Southwestern coast of Ukraine. It is noted as 96 feet. Beside it are seamarks. These landmarks aide navigation.

A significant factor to navigation is the prime meridian. In the early 19th century, the Russian militray did not use Greenwich as the prime meridian for its cartography. Instead, Manganari used the Pulkovo Meridian as the prime meridian, which was the practice in Russia at the time. The Pulkovo meridian is located at the Pulkovo Observatory in Saint Petersburg. In the spirit of the reforms in Alexander’s II reign, the later editions adopted Greenwich.

Nikolayev was a base of the Black Sea Fleet. It was also the location of the Depot of the Hydrographic Department of the Black Sea Fleet for the Imperial Navy. In1803, the depot was founded at the request of the Marquis de Traverse, Commander-in-Chief of the Black Sea Fleet at the time. It was established for the engineering needs of the fleet. There, the nautical charts of the Black Sea Atlas were drawn and compiled before engraving. Later editions of the charts were published in Nikolayev. [2]

Map Depot of the Hydrographic Department, Black Sea Fleet, Imperial Russian Navy, Nikolyaev. Click the link to learn more!

Later editions borrow from Vice-Admiral Thomas Abel Brimage Spratt (1811-1888). Spratt had an extensive career in the British Navy as an officer, hydrographer, and geologist. He produced a repertoire of nautical charts for the British Admiralty. He was a fellow of the Royal Geographical Society of London, the Zoological Society of London, the Society of Antiquaries of London, the Royal Society of London. The Crimean War provided Britain with the opportunity to survey the Black Sea. The then Captain Spratt completed nautical surveys of the Black Sea during the war. In May of 1851, Captain Spratt was given command of the paddle steamer HMS Spitfire to survey the island of Crete. This was the ship he used in the 1850s for his surveying of the Black Sea as it is noted on the nautical charts of the later editions.

The conditions of the Treaty of Paris (1856) is a primary reason why the Russian Navy would use Spratt’s maps in their own nautical charts of the Black Sea. Given that the Russian Navy could not have fleet in the Black Sea after the Crimean War, the navy could not perform its own surveying in the Black Sea. This situation lasted until the abrogation of the Black Sea clause by the Treaty of London in 1870. For the latter half of the 1850s and through the 1860s, Russia was without a fleet in the Black Sea to do the surveying required for nautical charts. Thus, the Russian navy had to find other sources for the information that they could not gather themselves in the time period. One source would be the Spratt’s surveys. By 1870, when Russia could rebuild the Black Sea Fleet, the most recent Russian survey of the Black Sea was Manganari’s atlas. However, the atlas had been published in 1841-1842 with surveys from the 1820s and 1830s. Spratt’s work was more recent dating to the 1850s. For that reason, Spratt’s work was included in the later editions of the 1880s and 1890s.

The legacy of Captain Manganari carried through one century into the next. His charts for the Black Sea Atlas that he surveyed in the 1880s would be used as a basemap for later editions. Even the Soviets used Managanari’s charts in the 1920s, almost century after Manganari published the Black Sea Atlas. The Black Sea has historically been signifcant for trade and militrary power. It has always has been a politcally contentious region, and remains so to this day. For this reason, the nautical charts of the Black Sea Atlas reflect the political situtiation and its military conflicts in the 19th century.

[1] Ibid.

[2] Васюков, Евгений ; Архитектура Николаева. Депо карт. [Vasi͡ukov, Evgeniĭ ; Nikolayev Architecture. Map Depot.] http://archmykolaiv.com/depo-kart/.

Imperial Russian Nautical Charts of the Black Sea Atlas at the AGSL Part I

By Josephine Miller

The Crimean War: Loss of the Black Sea Fleet and Reform

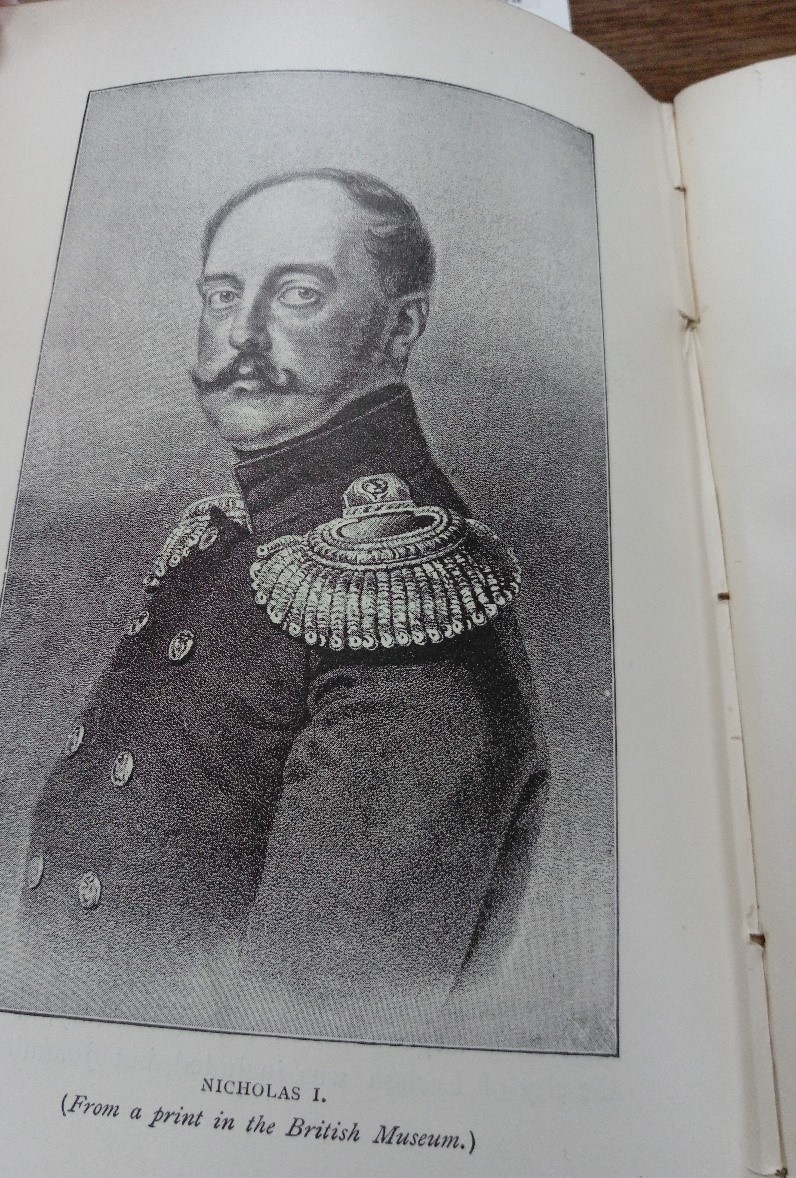

Tsar Alexander II (1818-1881) ascended to the throne on February 19 1855. He succeeded his father Tsar Nicholas I, who died at the age of 58 while Russia was losing the Crimean War (1853-1856). The war was fought between the Russian Empire and the alliance of the Ottoman Empire, Great Britain, France, and Sardinia. Alexander II came to the throne at the age of 36 at the end of the war. In the beginning of his reign, the young tsar was forced to face to the defeat of the Russian Empire. The Treaty of Paris was signed on March 30 1856, officially ending the Crimean War.

In the treaty, Russia ceded the mouth of the Danube and some of Bessarabia to the Ottomans. Additionally, Russia accepted the neutralization of the Black Sea. Neutralization meant not maintaining a navy or coastal fortifications in the Black Sea. In addition, Russia withdrew from the Danube Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia and accepted an international commission to oversee navigation of the Danube. Russia also forfeited its claim as protectorate of Orthodox Christians in the Holy Land and in the Ottoman Empire. The Crimean War was a great defeat for the Russian Empire, so much so that one rumor circulated that Nicholas I had poisoned himself. The war signified the decline of Russia’s influence in Southeastern Europe and the Near East. [1] As Russia was losing the war and Nicholas I approached death, he requested his funeral to be modest and the period of mourning to be as brief as possible. [2]

The defeat of Crimea was pivotal moment for Russian history. Notably, the Black Sea has historically been of great political importance for Russia, given its warm water ports. The defeat made a deep impression on the young Tsar Alexander II. He began his reign having to deal with the consequences of his father’s reign. Nicholas I had been a conservative autocrat who believed it was his sacred duty to uphold tradition. Under Nicolas I, Russia remained frozen in time. His rule is regarded as a conservative reaction to the Enlightenment. This reaction or rejection is best explained by his doctrine on Official Nationality (Теория официальной народности), which was based on the Triad “orthodoxy, autocracy, and nationalism” (Православие, самодержавие, народность).

The conservative disposition of Nicholas I is seen as the primary reason for the defeat in Crimea by the reformers. Before the war, Russia and its military enjoyed the positive reputation it had earned in its victory over Napoleon. However, while Nicholas I focused on upholding the tradition of the Triad, the West advanced scientifically and militarily. Consequently, when the war broke out, Russia faced the more advanced and modern armies of the West. The war revealed how lacking and inefficient the Russian military was in comparison to the West. The inefficient bureaucracy of the military, the lack of modern technology, and corruption were all examples of the inadequacies of the military. The outdated Russian military was frozen in the Napoleonic era, while the Allies had advanced into the Victorian era.

The industrialization in the West created a technological gap between Russia and the West, in particular, Russia and Great Britain. Great Britain was Russia’s primary imperial rival at the time. Technologically, the world had changed quickly in the middle of the 19th century. The period saw new technological innovations such as railroads, telegraphs, improved steam engines, and improvements in steel and iron. Significantly, Great Britain had the capability to import food and raw materials from around the world, allowing the mass production of consumer goods. Furthermore, the expanding of education in Western society accommodated this industrialization; Russia, on the other hand, lagged behind in all of these areas.

Lagging behind proved to be Russia’s disadvantage in the war. The fighting in the Crimean War revealed these disadvantages in the Russian military. Russia’s fleet of sailing ships could not fight against the steamships of Britain and France. Moreover, the Russian military relied on serfs for soldiers. Serfs could not provide the needed gunpowder and shells for battle. Ultimately, Russian soldiers marched into battle with smoothbore muskets, only to face the long-range artillery fire of the allies. [3]

In the aftermath of Crimea, reform found supporters from both the Slavophiles and the pro-Western factions. Both had been greatly upset by the defeat. The Slavophiles saw war against the Ottomans as a crusade for Orthodox Christianity and for Constantinople. Whereas, the Westernizers were dismayed by Russia losing its preeminent status as a European power that it had earned after the Napoleonic wars.

Alexander II began his reign as a proponent of reform, both militarily and politically. His most famous reform was the abolishment of serfdom, earning him the title the Tsar-Liberator or Alexander the Liberator. Alexander II was not the first tsar that wanted to end serfdom, but the Crimean War provided the opportunity. The serf army proved to be ineffective. If Russia were to modernize it would need to industrialize, which would also include a citizen army. The institution of serfdom inhibited both modernization and industrialization. Serfdom kept the Russian economy agrarian and stifled the innovation needed for industrialism. In the following decade, Alexander II enacted political and military reforms in order to modernize Russia and its military.

Revival of the Black Sea Fleet

Nonetheless, the treaty of Paris limited naval ambition due to the demilitarization stipulation in the treaty. Opportunity would arise in 1870s for the Black Sea Fleet. On September 1, 1870, Emperor Napoleon III surrendered to Prussia. During the Franco-Prussian War, Russian remained officially neutral. However, according to the memoirs of Count Dmitry Milyutin, Field Marshall and Minister of War Alexander II sent St. George Crosses to Prussian officers and a congratulatory telegram to King Wilhelm I after Prussian victory. Notably, Wilhelm I was the maternal uncle of Alexander II. Additionally, Russian officers served in the Prussian army. [4]

The Franco-Prussian War led to the establishment of the German Empire. Upon unification, King Wilhelm I of Prussia became German Emperor. Otto von Bismarck, Chancellor of the new German Empire, wanted to gain favor with Russia due to the mutual threat of Polish nationalism. Bismarck sent Count Constantin von Alvensleben to Russia in order to come to an agreement on cooperation against Polish rebellion. [5]

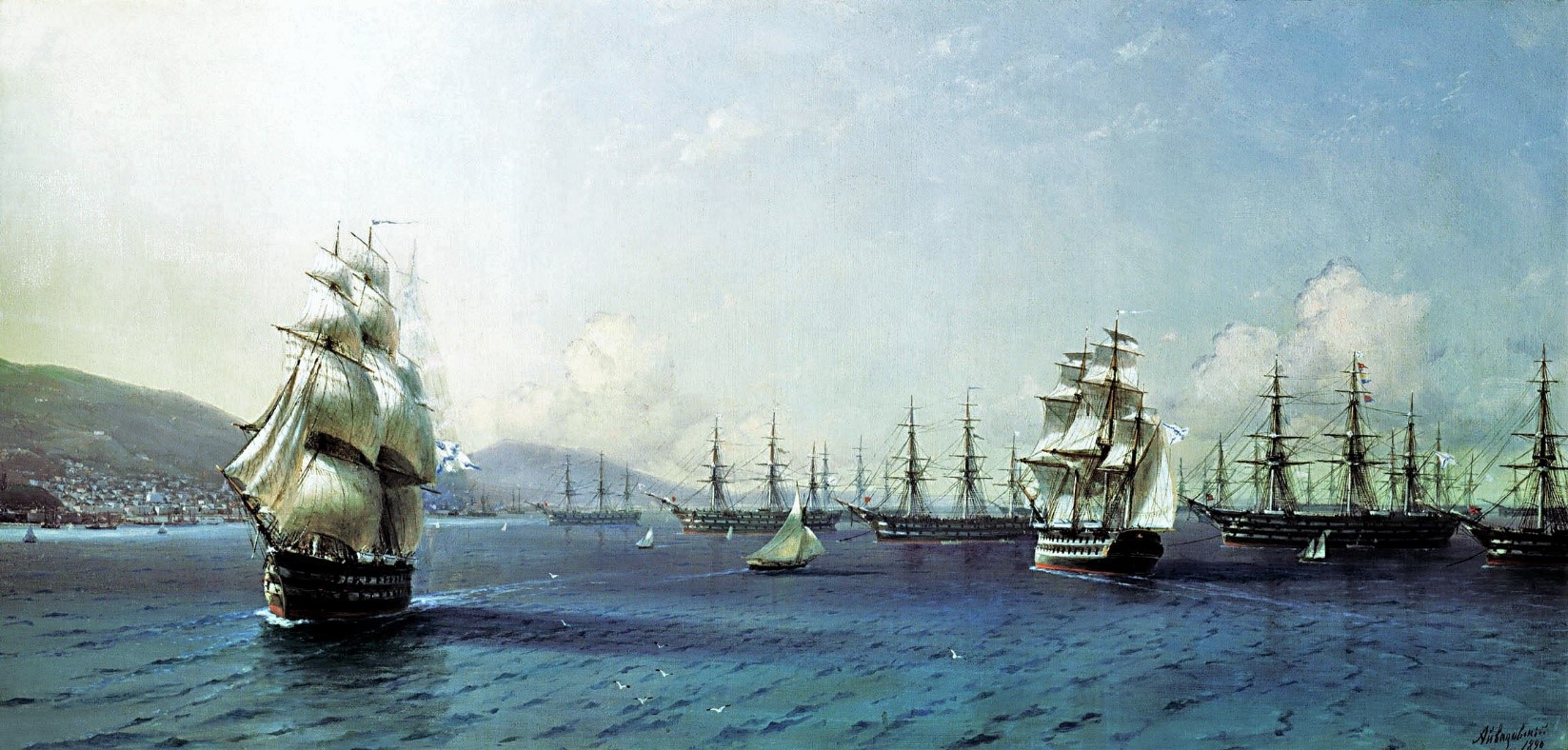

Black Sea Fleet in the Bay of Theodosia, just before the Crimean War, 1890, Ivan Aivazovsky,

Feodosiya National Gallery I. K. Aivazovsky

German rapprochement aided Russia in a more important foreign policy objective for Russia: the Black Sea. In 1870, Prince Alexander Gorchakov, Foreign Minister, used France’s defeat to denounce the Black Sea clause of the Treaty of Paris (1856). Gorchakov’s denouncement included the refusal to uphold the clause. In his justification, Gorchakov cited to Turkey violations of the treaty and he argued that the conditions of warfare have become more dangerous since 1856 due to the more destructive armaments. Bismarck supported Gorchakov on the Black Sea clause. Though Britain protested, the European powers agreed to it through the Treaty of London in 1871, which abrogated the Black Sea clause of the Treaty of Paris. This allowed Russia to rebuild the Black Sea Fleet and military fortifications on the Black Sea. [6]

Egor Pavlovich Manganari (Егор Павлович Манганари)

The Atlas of the Black Sea (Атлас Чёрного Моря) was published between 1841 and1842. The surveying for the atlas was led by Captain-Lieutenant Egor Manganari (1796-1868). He was the eldest son of Panayot Manganari, (also known as Pavel Manganari in Russian). Panayot Manganari was a Greek nobleman and immigrant to the Russian Empire from the Greek island Chios. He immigrated to Russia due to conflict with the Ottomans, taking advantage of the Catherine the Great’s invitation to settle Greeks in the Southern Russian Empire. He married Alexandra Timofeevna and they had six children: three daughters, Maria, Ekaterina, and Anastasia, and three sons who served as officers in the Black Sea Fleet, Egor, Ivan, and Mikhail. The family first lived in Yevpatoriya and later in Nikolayev. [7]

Egor Manganari served in the Black Sea Fleet of the Imperial Russian Navy as a naval officer and hydrographer. He attended the Black Sea Navigational School in Nikolayev. There he studied Russian, English, classical subjects, and subjects related to geography such as mathematics, geodesy, navigation, and cartography.[8]

In 1813, he entered the Black Sea Fleet as a Navigation Assistant. By 1816, he received the rank of First Officer Midshipman and was later promoted to Lieutenant in 1821. He was appointed commander of the rig Nikolai (Николай) where he produced an inventory the Dnieper Estuary and the Bug River. His work was highly praised, earning him the Order of Saint Anna, 3rd Class, and the commission to survey the Azov and Black Sea. He commanded the Nikolai until 1827, when he received the command of the yacht Golubka (Голубка). The expedition of the Black Sea was launched in 1826 and continued for ten years. Manganari still participated in the Russo-Turkish War (1828–29), for which he was awarded the Order of Saint Vladimir, 4th Class. In 1833-1834, during the Caucasian War, he also did hydrographic surveys of the Caucasus, for which he was awarded the Order of Saint Stanislav, 2nd class. [9]

By 1838, he had been promoted to lieutenant-colonel and completed his survey of the Black Sea and Azov Sea. His nautical charts were supported by the Admiral Mikhail Lazarev, Commander of the Black Sea Fleet. After the Black Sea expedition concluded, he was granted permission by the Navy to publish them. The nautical charts were brought to Saint Petersburg to be engraved and published as an atlas. After the publication of the atlas, Manganari was awarded the Order of Saint George, 4th class. Manganari continued to do hydrographic surveying of the Black Sea after the publication of the atlas. In 1849, he received the rank of major-general and was appointed as the director of the Lighthouses of the Black Sea and Azov Sea. Manganari remained at that post until he retired in 1856. [10] [11]

[1] Nicholas V. Riasanovsky and Mark D. Steinberg, A History of Russia, (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), 333-336.

[2] Kaputina, Tatiana Aleksandrovna. “Nicholas I.” In The Emperors and Empresses of Russia: Rediscovering the Romanovs, (Armonk, New York: M. E. Sharpe), 292.

[3] Russia in the Nineteenth Century: Autocracy, Reforms, and Social Change, 1814-1914, (Armonk, New York: M.E. Sharpe) 85.

[4] Ibid. 161.

[5] Nicholas V. Riasanovsky and Mark D. Steinberg, A History of Russia, (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), 380.

[6] Russia in the Nineteenth Century Autocracy, Reforms, and Social Change, 1814-1914, (Armonk, New York: M.E. Sharpe) 161.

[7] Выдающиеся морские гидрографы братья Манганари. Часть I. Николаевский Базар. [Outstanding Marine Hydrograph Brothers. Part I, Nikolayev Bazar].

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Üçsu, Kaan. “Cartographies of the ‘Eastern Question’: Some Considerations on Mapping the Sea of Marmara and the Black Sea in the Nineteenth Century.” In Philosophy of Globalization, (Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter, 2018) 259-260.