history

The Cassini Atlas

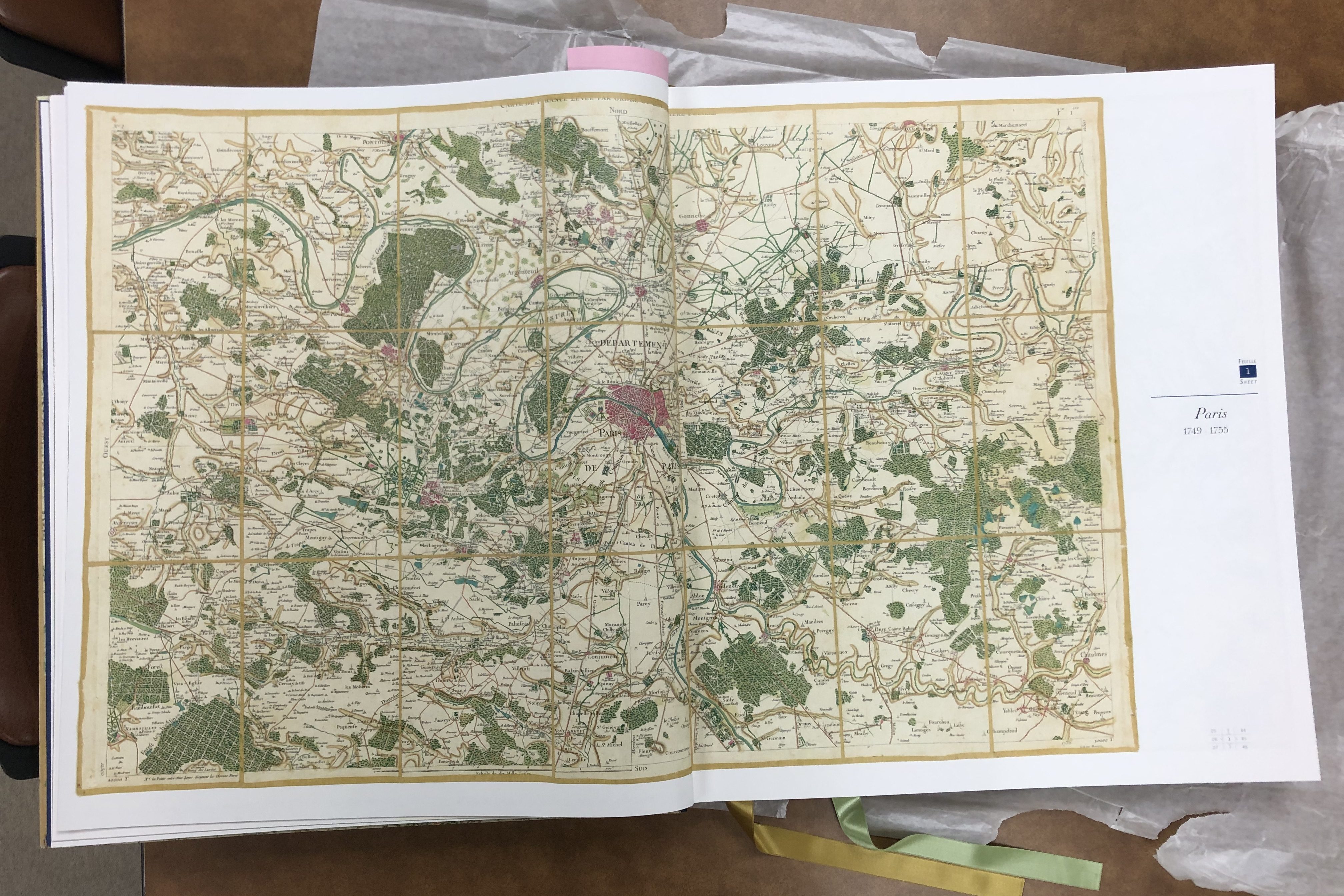

The AGSL recently added a treasure to our collections: a bound reproduction of hand-colored editions of the Cassini Map, released in a limited edition this year. This book is a massive (22.4×26.2 inches when closed!), masterful edition of one of the most influential mapping projects in Western history: the Cassini Family’s map of France.

The Cassini maps are the result of the work of four generations of astronomers, geometers, and cartographers in the Cassini Family. Cassini I, Giovanni Domencio, was an astronomer who worked for Louis XIV at the Paris Observatory. Using his knowledge of the stars and planets’ movements, he was the first to accurately measure distances on Earth using triangulation and geodetic measurements —a method we still use in mapping today! Cassini I also proposed a way to standardize longitude, a necessity for both navigation and conveying distance on maps.

Cassini I, his son, and his grandson all worked on creating a map of France using their new, scientific mapping method, and the result was the first accurate outline map of France, presented to the King in 1744. Cassini III thought that this map would be the end of their project, but Louis XV had bigger plans: he wanted the Cassinis to create detailed, topographic maps of each part of his nation.

Over about 30 years, this mapping project would give us the maps bound in the atlas just added to the AGSL’s collections. Cassini III and Cassini IV (after 1784) oversaw the process with care: they had ten different teams of surveyors spread out over the country at any given time, asking them to make extensive notes on both the geodetic measurements they were making and topographic and toponymic information like physical landmarks, church locations, and place names to include in the maps. The result was 182 sheets which measured 65×95 centimeters each, covering the entirety of France.

While the maps would have been an impressive point in the history of mapping because of the size of the project and the innovation in measurements alone, they also left an important legacy in the political and social histories of mapping. The Cassinis’ massive mapping endeavor was initially made possible because France’s kings wanted accurate, comprehensive maps to help them govern, quantify, and tax the nation they ruled. To make that possible, the Cassinis not only imposed the lines of measurement on France, they also developed and standardized what historian Jerry Brotton calls a “new language of cartography” through their maps, where standardized symbols, lettering, and notations made the culturally and linguistically diverse county seem like a unified nation—and one happily overseen by a monarch (Brotton, 324).

But before the maps were completed, the French Revolution altered the course of France’s nationhood, and of the Cassinis’ project. In 1793, the National Assembly ‘nationalized’ the map, forbidding the sheets that had already been published from being sold and confiscating all the Cassinis’ engraved plates to prevent more copies being made. From this point on, the maps were seen not just as navigational tools for the public, but as a way to unify the diverse peoples living within the national lines of France so that they could more effectively be governed. It was Napoleon’s Department of War who finished printing the full series of maps in 1815, helping the infamous emperor re-shape France’s identity for himself.

If you’d like to see our stunning copy of the Cassini’s historic atlas for yourself, stop by the AGSL sometime this summer! To read more about the Cassini map, check out chapter 9 of Jerry Brotton’s A History of the World in Twelve Maps or the website of the publisher of our new atlas. Or you can schedule an appointment to view two original sheets of the Cassinis’ map using our Rare Materials Viewing Form!

Guest Post: The Russo-Japanese War

Today, we are delighted to showcase an insightful guest essay by Violet Wakefield, a student at UWM specializing in History with a minor in Anthropology. During the spring semester, Violet engaged in HIST 596, “Maps as Historical Sources,” a UWM history class embedded in the AGSL

Referred to by some modern historians as “World War Zero,” the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905 is often overlooked in American accounts of the 20th century. The war was one of several military conflicts that marked the end of Russia’s eastward expansion, the most recent at the time being the Boxer Rebellion in China in 1900. Unlike their far more informal conflict with a rapidly declining Chinese kingdom, growing tensions between Russia and the rising power of Japan over rights to Manchuria and Korea had ripple effects that could be felt for decades to come. The complex network of imperial rivalries and mutual defense treaties that would eventually plunge the world into the Great War a decade later generated diplomatic tensions all across Eurasia and into the United States as early as 1903, long before a single bullet was fired. This map1, creatively titled “1904 War Map of Russia and the Continent of Asia,” printed by the prominent Chicago firm Rand-McNally at the war’s outbreak in winter of 1904, sheds light on the American view of this distant, seemingly inconsequential conflict.

China, in spite of its weak economy throughout the Century of Humiliation, was viewed by American and European capitalists alike as a potentially limitless market, a future “oriental version of the United States.”2 As a result of this belief, contemporaries around the world paid close attention to the Russo-Japanese war and its aftermath. Western interest in the war was, however, still motivated in part by anxieties surrounding the treaties of mutual defense between the Great Powers. Diplomatic pressure was placed on France and Britain to aid the Russians and Japanese, respectively, through the Dual Entente of the 1890s and Anglo-Japanese Alliance of 1902. American interest in particular was purely financial, however. The 19th century project of American imperialism in the Pacific required an informal alliance with the Japanese, and the fear regarding a Russian victory was that of a wider war between European empires. It was widely believed by American diplomats in China that if, because of the Russian foothold established in Manchuria, the French and German empires would also seek to control larger portions of Chinese territory as compensation. Only the Japanese and British, the most successful foreign powers in China in the late 19th century, were seen as standing in Russia’s way.3

As the war rolled on and Japan gained the clear upper hand, the Roosevelt administration was not brought into the 18 month-long conflict until peace negotiations began in 1903. Reflecting the anxieties held by many that the war would be a spark in a global conflict, the most prominent features of Rand-McNally’s map are the population sizes of various major cities across Asia. None of the countries listed on the map were actively attacked by either power over the course of the war, but at this early date, it was unknown if that was a possibility. As European nation-states entered the modern era, more emphasis was placed on the depiction of statistical data.4 Maps, by the turn of the 20th century, were only one of many tools for planning a war. Battlefield maps were far less important to diplomats and generals than the numbers, measurements, and troop movements. As such, both Russian and Japanese naval and infantry capabilities are featured prominently in this map’s top and bottom sidebars. European military strategy throughout the 19th century gradually began to shift its emphasis from specific locations and terrain to the broader landscape a war was being fought across, from battles to the front.5 American military strategy in the years following the Civil War was also similarly focused on the broader front of a war. This can be seen in the lack of specific battlegrounds on the map. The war did however, through fictionalized English language accounts and rapidly produced illustrated volumes, succeed in capturing the imagination of Anglo-American consumers.6

Since the Spanish-American War of 1898, which was similar in significance on the international stage to the Russo-Japanese war, the American public in particular developed an insatiable appetite for war maps. This map is just one such product made to fill this new niche in the American map market, dense with information about the far-flung empires of Asia and their military capabilities. Historian Susan Schulten makes note of the prominence of the Chicago map-making firms in the last decades of the 19th century, as Chicago’s placement near the frontier of the urban North allowed it to service settlers in the western half of the continent far easier than cities like Baltimore or New York.7 Chicago’s mapmaking industry was shaped by the early demand for political maps of Western North America, and political maps remained the most commonly purchased consumer level map for decades after westward expansion came to an end. While settlers in American territories of 1904 did not necessarily know the threat the war in Asia could have had on their livelihoods, they may well have encountered this particular map as a part of Rand-McNally’s latest print run in a general store, a market, or perhaps even decorating the home of a friend.

Bibliography

“1904 War Map of Russia and the Continent of Asia; 1904 War Map of Japan, Korea and China” (Chicago: Rand McNally and Company, 1904).

David Schimmelpenninck van der Oye, “Rewriting the Russo-Japanese War: A Centenary Retrospective,” The Russian Review 67, no. 1 (2008), pages 78 – 87.

Edward B. Parsons, “Roosevelt’s Containment of the Russo-Japanese War,” Pacific Historical Review 38, no. 1 (1969): pages 21 – 44.

Matthew Edney, “Mapping Parts of the World,” in Maps: Finding Our Place in the World, James R. Akerman and Robert W. Karrow, Jr., ed. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007), pages 117 – 157.

Michael Friendly and Gilles Palsky, “Visualizing Nature and Society,” in Maps: Finding Our Place in the World, James R. Akerman and Robert W. Karrow, Jr, ed. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2007), pages 207 – 254.

Susan Schulten,“Maps for the Masses, 1880-1900,” in The Geographical Imagination in America, 1880-1950, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001), pages 17 – 44.

- “1904 War Map of Russia and the Continent of Asia; 1904 War Map of Japan, Korea and China” (Chicago: Rand McNally and Company, 1904). ↩︎

- Edward B. Parsons, “Roosevelt’s Containment of the Russo-Japanese War,” Pacific Historical Review 38, no. 1 (1969): page 23 ↩︎

- Parsons, “Roosevelt’s Containment of the Russo-Japanese War,” page 27 ↩︎

- Michael Friendly and Gilles Palsky, “Visualizing Nature and Society,” in Maps

- Matthew Edney, “Mapping Parts of the World,” in Maps

- David Schimmelpenninck van der Oye, “Rewriting the Russo-Japanese War: A Centenary Retrospective,” The Russian Review 67, no. 1 (2008), page 82. ↩︎

- Susan Schulten,“Maps for the Masses, 1880-1900,” in The Geographical Imagination in America, 1880-1950, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001), page 23. ↩︎