Alexander II

Imperial Russian Nautical Charts of the Black Sea Atlas at the AGSL Part I

By Josephine Miller

The Crimean War: Loss of the Black Sea Fleet and Reform

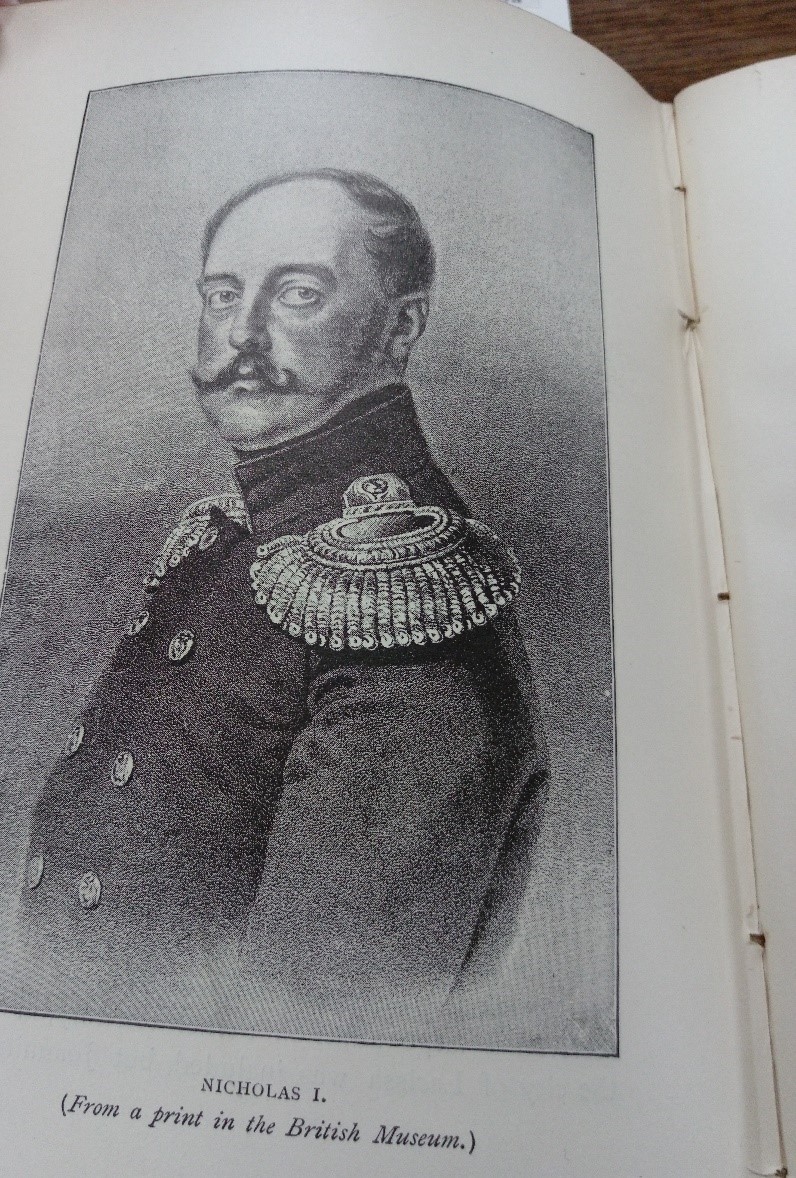

Tsar Alexander II (1818-1881) ascended to the throne on February 19 1855. He succeeded his father Tsar Nicholas I, who died at the age of 58 while Russia was losing the Crimean War (1853-1856). The war was fought between the Russian Empire and the alliance of the Ottoman Empire, Great Britain, France, and Sardinia. Alexander II came to the throne at the age of 36 at the end of the war. In the beginning of his reign, the young tsar was forced to face to the defeat of the Russian Empire. The Treaty of Paris was signed on March 30 1856, officially ending the Crimean War.

In the treaty, Russia ceded the mouth of the Danube and some of Bessarabia to the Ottomans. Additionally, Russia accepted the neutralization of the Black Sea. Neutralization meant not maintaining a navy or coastal fortifications in the Black Sea. In addition, Russia withdrew from the Danube Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia and accepted an international commission to oversee navigation of the Danube. Russia also forfeited its claim as protectorate of Orthodox Christians in the Holy Land and in the Ottoman Empire. The Crimean War was a great defeat for the Russian Empire, so much so that one rumor circulated that Nicholas I had poisoned himself. The war signified the decline of Russia’s influence in Southeastern Europe and the Near East. [1] As Russia was losing the war and Nicholas I approached death, he requested his funeral to be modest and the period of mourning to be as brief as possible. [2]

The defeat of Crimea was pivotal moment for Russian history. Notably, the Black Sea has historically been of great political importance for Russia, given its warm water ports. The defeat made a deep impression on the young Tsar Alexander II. He began his reign having to deal with the consequences of his father’s reign. Nicholas I had been a conservative autocrat who believed it was his sacred duty to uphold tradition. Under Nicolas I, Russia remained frozen in time. His rule is regarded as a conservative reaction to the Enlightenment. This reaction or rejection is best explained by his doctrine on Official Nationality (Теория официальной народности), which was based on the Triad “orthodoxy, autocracy, and nationalism” (Православие, самодержавие, народность).

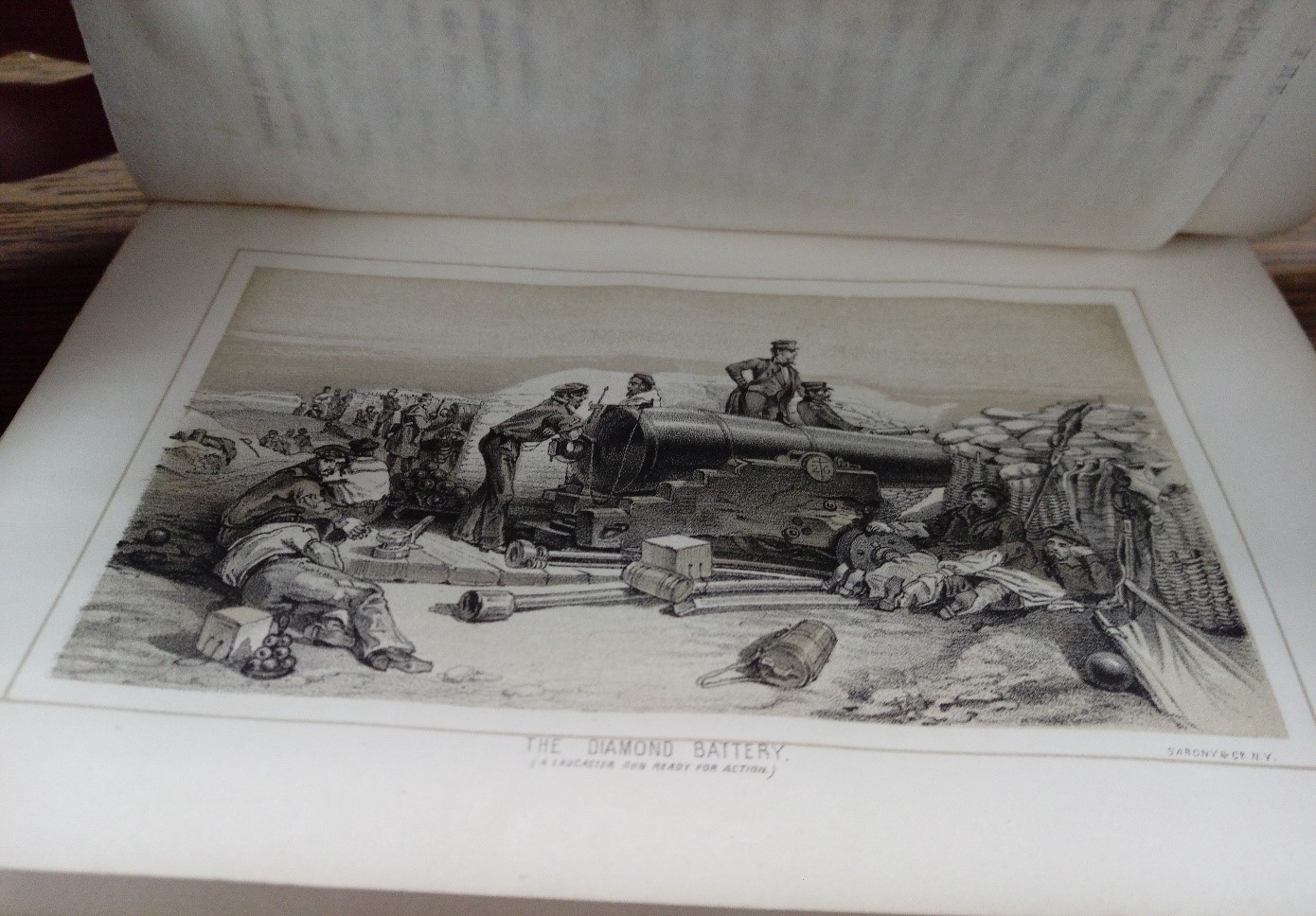

The conservative disposition of Nicholas I is seen as the primary reason for the defeat in Crimea by the reformers. Before the war, Russia and its military enjoyed the positive reputation it had earned in its victory over Napoleon. However, while Nicholas I focused on upholding the tradition of the Triad, the West advanced scientifically and militarily. Consequently, when the war broke out, Russia faced the more advanced and modern armies of the West. The war revealed how lacking and inefficient the Russian military was in comparison to the West. The inefficient bureaucracy of the military, the lack of modern technology, and corruption were all examples of the inadequacies of the military. The outdated Russian military was frozen in the Napoleonic era, while the Allies had advanced into the Victorian era.

The industrialization in the West created a technological gap between Russia and the West, in particular, Russia and Great Britain. Great Britain was Russia’s primary imperial rival at the time. Technologically, the world had changed quickly in the middle of the 19th century. The period saw new technological innovations such as railroads, telegraphs, improved steam engines, and improvements in steel and iron. Significantly, Great Britain had the capability to import food and raw materials from around the world, allowing the mass production of consumer goods. Furthermore, the expanding of education in Western society accommodated this industrialization; Russia, on the other hand, lagged behind in all of these areas.

Lagging behind proved to be Russia’s disadvantage in the war. The fighting in the Crimean War revealed these disadvantages in the Russian military. Russia’s fleet of sailing ships could not fight against the steamships of Britain and France. Moreover, the Russian military relied on serfs for soldiers. Serfs could not provide the needed gunpowder and shells for battle. Ultimately, Russian soldiers marched into battle with smoothbore muskets, only to face the long-range artillery fire of the allies. [3]

In the aftermath of Crimea, reform found supporters from both the Slavophiles and the pro-Western factions. Both had been greatly upset by the defeat. The Slavophiles saw war against the Ottomans as a crusade for Orthodox Christianity and for Constantinople. Whereas, the Westernizers were dismayed by Russia losing its preeminent status as a European power that it had earned after the Napoleonic wars.

Alexander II began his reign as a proponent of reform, both militarily and politically. His most famous reform was the abolishment of serfdom, earning him the title the Tsar-Liberator or Alexander the Liberator. Alexander II was not the first tsar that wanted to end serfdom, but the Crimean War provided the opportunity. The serf army proved to be ineffective. If Russia were to modernize it would need to industrialize, which would also include a citizen army. The institution of serfdom inhibited both modernization and industrialization. Serfdom kept the Russian economy agrarian and stifled the innovation needed for industrialism. In the following decade, Alexander II enacted political and military reforms in order to modernize Russia and its military.

Revival of the Black Sea Fleet

Nonetheless, the treaty of Paris limited naval ambition due to the demilitarization stipulation in the treaty. Opportunity would arise in 1870s for the Black Sea Fleet. On September 1, 1870, Emperor Napoleon III surrendered to Prussia. During the Franco-Prussian War, Russian remained officially neutral. However, according to the memoirs of Count Dmitry Milyutin, Field Marshall and Minister of War Alexander II sent St. George Crosses to Prussian officers and a congratulatory telegram to King Wilhelm I after Prussian victory. Notably, Wilhelm I was the maternal uncle of Alexander II. Additionally, Russian officers served in the Prussian army. [4]

The Franco-Prussian War led to the establishment of the German Empire. Upon unification, King Wilhelm I of Prussia became German Emperor. Otto von Bismarck, Chancellor of the new German Empire, wanted to gain favor with Russia due to the mutual threat of Polish nationalism. Bismarck sent Count Constantin von Alvensleben to Russia in order to come to an agreement on cooperation against Polish rebellion. [5]

Black Sea Fleet in the Bay of Theodosia, just before the Crimean War, 1890, Ivan Aivazovsky,

Feodosiya National Gallery I. K. Aivazovsky

German rapprochement aided Russia in a more important foreign policy objective for Russia: the Black Sea. In 1870, Prince Alexander Gorchakov, Foreign Minister, used France’s defeat to denounce the Black Sea clause of the Treaty of Paris (1856). Gorchakov’s denouncement included the refusal to uphold the clause. In his justification, Gorchakov cited to Turkey violations of the treaty and he argued that the conditions of warfare have become more dangerous since 1856 due to the more destructive armaments. Bismarck supported Gorchakov on the Black Sea clause. Though Britain protested, the European powers agreed to it through the Treaty of London in 1871, which abrogated the Black Sea clause of the Treaty of Paris. This allowed Russia to rebuild the Black Sea Fleet and military fortifications on the Black Sea. [6]

Egor Pavlovich Manganari (Егор Павлович Манганари)

The Atlas of the Black Sea (Атлас Чёрного Моря) was published between 1841 and1842. The surveying for the atlas was led by Captain-Lieutenant Egor Manganari (1796-1868). He was the eldest son of Panayot Manganari, (also known as Pavel Manganari in Russian). Panayot Manganari was a Greek nobleman and immigrant to the Russian Empire from the Greek island Chios. He immigrated to Russia due to conflict with the Ottomans, taking advantage of the Catherine the Great’s invitation to settle Greeks in the Southern Russian Empire. He married Alexandra Timofeevna and they had six children: three daughters, Maria, Ekaterina, and Anastasia, and three sons who served as officers in the Black Sea Fleet, Egor, Ivan, and Mikhail. The family first lived in Yevpatoriya and later in Nikolayev. [7]

Egor Manganari served in the Black Sea Fleet of the Imperial Russian Navy as a naval officer and hydrographer. He attended the Black Sea Navigational School in Nikolayev. There he studied Russian, English, classical subjects, and subjects related to geography such as mathematics, geodesy, navigation, and cartography.[8]

In 1813, he entered the Black Sea Fleet as a Navigation Assistant. By 1816, he received the rank of First Officer Midshipman and was later promoted to Lieutenant in 1821. He was appointed commander of the rig Nikolai (Николай) where he produced an inventory the Dnieper Estuary and the Bug River. His work was highly praised, earning him the Order of Saint Anna, 3rd Class, and the commission to survey the Azov and Black Sea. He commanded the Nikolai until 1827, when he received the command of the yacht Golubka (Голубка). The expedition of the Black Sea was launched in 1826 and continued for ten years. Manganari still participated in the Russo-Turkish War (1828–29), for which he was awarded the Order of Saint Vladimir, 4th Class. In 1833-1834, during the Caucasian War, he also did hydrographic surveys of the Caucasus, for which he was awarded the Order of Saint Stanislav, 2nd class. [9]

By 1838, he had been promoted to lieutenant-colonel and completed his survey of the Black Sea and Azov Sea. His nautical charts were supported by the Admiral Mikhail Lazarev, Commander of the Black Sea Fleet. After the Black Sea expedition concluded, he was granted permission by the Navy to publish them. The nautical charts were brought to Saint Petersburg to be engraved and published as an atlas. After the publication of the atlas, Manganari was awarded the Order of Saint George, 4th class. Manganari continued to do hydrographic surveying of the Black Sea after the publication of the atlas. In 1849, he received the rank of major-general and was appointed as the director of the Lighthouses of the Black Sea and Azov Sea. Manganari remained at that post until he retired in 1856. [10] [11]

[1] Nicholas V. Riasanovsky and Mark D. Steinberg, A History of Russia, (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), 333-336.

[2] Kaputina, Tatiana Aleksandrovna. “Nicholas I.” In The Emperors and Empresses of Russia: Rediscovering the Romanovs, (Armonk, New York: M. E. Sharpe), 292.

[3] Russia in the Nineteenth Century: Autocracy, Reforms, and Social Change, 1814-1914, (Armonk, New York: M.E. Sharpe) 85.

[4] Ibid. 161.

[5] Nicholas V. Riasanovsky and Mark D. Steinberg, A History of Russia, (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), 380.

[6] Russia in the Nineteenth Century Autocracy, Reforms, and Social Change, 1814-1914, (Armonk, New York: M.E. Sharpe) 161.

[7] Выдающиеся морские гидрографы братья Манганари. Часть I. Николаевский Базар. [Outstanding Marine Hydrograph Brothers. Part I, Nikolayev Bazar].

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Üçsu, Kaan. “Cartographies of the ‘Eastern Question’: Some Considerations on Mapping the Sea of Marmara and the Black Sea in the Nineteenth Century.” In Philosophy of Globalization, (Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter, 2018) 259-260.